Could there be aliens living inside Europa, Callisto, or Ganymede?

Colossal oceans slosh beneath the surface of three of Jupiter's largest moons, melted by the planet's enormous gravity and other processes. Even though they're completely sealed off from sunlight, chemical interactions on the seafloor could be the perfect location for microbial life.

Let's journey to the Solar System's largest planet to get to the bottom of astronomy's most burning question: Is there life outside of Earth?

TRANSCRIPT

What on Earth are we looking at?

Well, we're not on Earth at all—we're on Jupiter.

The fifth planet from the Sun is a swirling mix of gas and super dense fluid. It's also massive—like twice every other planet massive.

With so much mass, Jupiter has serious gravitational pull, helping it gather a big family of moons.

These four are pretty big themselves, close to and even exceeding the size of the planet Mercury.

Io is a harsh volcanic hellscape, blasted by Jupiter's radiation, with lakes of molten lava flowing across the surface.

Ocean Moons

But the other three are even more interesting, because they are ocean moons, with liquid water sloshing beneath the surface.

On Earth, water always means life. So what about here?

When you think of liquid water, which world comes to mind?

Earth is the obvious answer. After all, it's covered in the stuff. But only covered.

Most of the planet is rock, and while that's important for life, it's not enough.

Ganymede

Ganymede, on the other hand, is mostly water.

The top layer is iced over; after all, it's freezing out in Jupiter's orbit.

But leftover heat from Jupiter's gravity and the moon's formation have melted a global ocean deep underneath.

Or rather, oceans, plural, with layers of ice and liquid stacked like a club sandwich.

If we're looking for life, we should start at the bottom, where super salty water touches a rocky seafloor.

That matters, because we think that direct contact between ocean and rock is crucial for the emergence of life.

Our problem is that that ocean is really far down, virtually impossible to reach with any kind of probe for life detection.

But that might be a blessing, because in theory, we could send humans to Ganymede.

Unlike every other moon, it has a magnetic field. Not a strong one, but enough to shield from the worst of the Sun and Jupiter's radiation.

With all the water you'd ever need and plenty to explore, it would make a good base camp.

But we'll get back to that. We're looking for life, and Ganymede is not looking like the best option.

So let's move to another of Jupiter's ocean moons, Callisto.

Callisto

From a distance, Callisto is a cratered mess.

In fact, it's the most heavily cratered object in the Solar System, with virtually no tectonic activity to renew the surface.

The moon is far enough away from Jupiter that it never got particularly hot, so it doesn't have the kind of distinct layers we see on Ganymede.

What it does have is another ocean, kept liquid by some combination of ammonia, salt, or other antifreeze.

It's not the best prospect for life because unlike Ganymede, none of the ocean directly touches rock.

That makes Callisto's ocean completely sealed off from the rest of the universe, ancient and unchanged from its formation.

But while it might not be habitable for aliens, it might be habitable for us.

While Callisto doesn't have a magnetic field of its own, Jupiter does, and it's protected from the planet's own radiation by its distance.

In fact, a NASA paper chose Callisto as the best spot to send humans for outer planet exploration.

Completed in about five years, astronauts would spend 30 days on the moon's surface.

While there, they could operate robots in real time, searching for life on our final ocean moon: Europa.

Europa

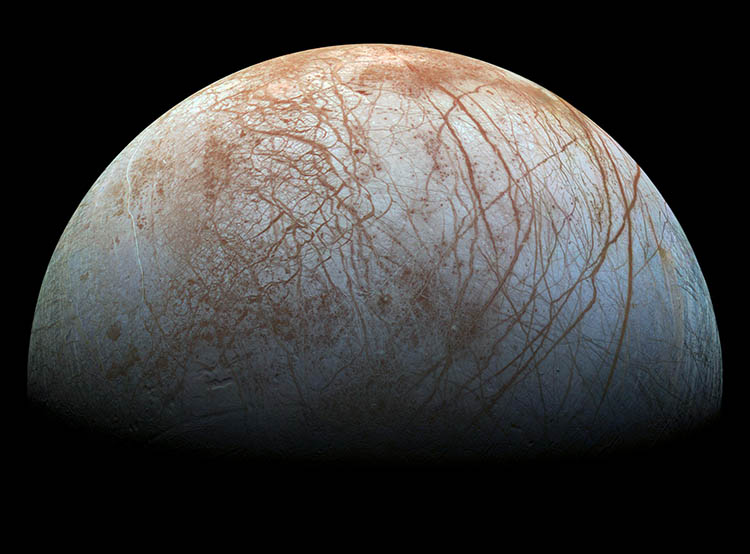

Viewed from orbit, Europa looks like a perfect sphere, smooth as a billiard ball.

But look a little closer and things get chaotic. Fractured blocks of ice jostle for ground, pushed and pulled by convective currents.

Dark streaks called lineae stretch for thousands of kilometers, forming a vast spider's web.

These are the hallmarks of a young surface, geologically active.

With a comparatively thin, icy crust, Europa's waters push fresh, dirty ice to the surface in a constant state of renewal.

That's caused in part by enormous tidal forces on the moon, which cause the ocean to rise and fall by up to 30 meters.

The ocean itself is colossal, with significantly more water than all of Earth's oceans combined.

And unlike Ganymede or Callisto, there's no club sandwich here: It's liquid all the way down to a silicate mantle seafloor.

That means that all-important interaction between water and rock, making Europa a top destination for astrobiologists.

If we did find life there, what would it look like?

You might be thinking of glowing jellyfish or orca whales, but it's a safer bet to think small: single-celled organisms like bacteria.

Feeding off chemical processes on the seafloor, life on Europa would have a steady stream of energy to siphon.

So, at least in the Jovian system, Europa is our best bet for finding life. How in the world are we going to do that?

Europa Clipper

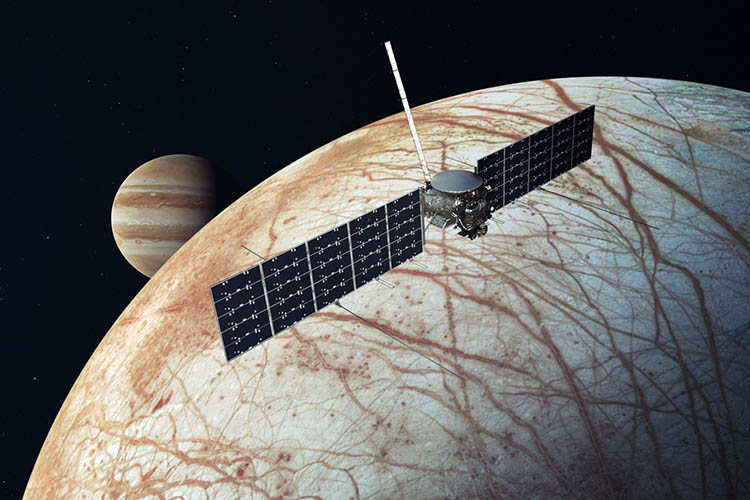

Enter the Europa Clipper.

Launching around 2024, this NASA's spacecraft would spend three years in the Jovian system.

It would fly by Europa 45 times, skimming the surface as close as 25 kilometers.

Clipper is packed with instruments, to measure the ocean's salinity, map the crust, look for warm patches, and analyze particles for organic compounds.

If Clipper does find life, it would have evolved completely separately to life on earth, lending evidence to the idea that life is common throughout the universe.

ESA's JUICE

But what about our other ocean moons? They're getting a mission too, with JUICE.

The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer is the first outer planets mission completely designed and run by the European Space Agency.

It's scheduled to launch in April 2023, arriving in the Jovian system around 2031.

Unlike NASA's Clipper, JUICE will take a close look at all three ocean moons, focused on internal structure, surface features and exospheres.

After flybys of Callisto and Europa, JUICE will enter into orbit around Ganymede, spending nearly a year with the giant moon.

Conclusion

Water is abundant in our solar system, and liquid water is more common than you might think.

But as far as we've come in understanding our neighborhood, we still haven't answered the ultimate question: Is life hiding near the outer planets?

With the help of NASA and the European Space Agency, the answer to that question is closer than ever.

Sources and further reading:

Ocean Worlds at NASA

Ganymede In Depth at NASA

Callisto In Depth at NASA

Europa In Depth at NASA

NASA's Europa Clipper at NASA

JUICE at ESA